I am sure you have heard by now, the fish are already starting to utilize the habitat up above where the projects used to be located. It is awesome, and it is going to keep getting better. I just want to say that I know in my heart that your film and the work you did had a huge impact on the ways things turned out and I am still very grateful to you for that work you did.

Rachel Hagaman (Kowalski), Economic Director, Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe

Background

Unconquering the Last Frontier is the Epic Story of the Damming and Undamming of the Elwha River. Filming began in 1993 in Port Angeles, Washington. Production continued for five years, through 1997. The Filmmakers’ mission was to document the efforts of the tribal community and others, to preserve the genetics of the last wild salmon, while the political drama over funding, related to Elwha dam removal played out at the federal level.

The process of making this film created a solid perspective, showing both sides of the issue in depth. The narrative is revealing of the larger scope of need for preserving the what we have left of our nation’s wild places. Our team saw the benefit of redeeming a river, by removing the harness of misguided, industrial encroachment.

The film was released, during special screenings in the San Francisco Bay Area and in Western Washington, to public television stations and to cable (Free Speech TV). A companion fine art photo exhibit, from photography commissioned by the National Park Service, (Large scale digital prints from film positive), was created and displayed in California and Washington. 2006-2008.

Patagonia headquarters, Ventura, CA, BC Space Gallery, Laguna Beach, CA, Seed Gallery, Thoreau Center for Sustainability, San Francisco, Odd Art Gallery, Port Angeles, WA.

The film itself was shot traditionally, using crystal-sync double-system. Eastman Kodak 16mm color negative film was exposed through a French made Eclair ACL 1.5 camera with Angenieux lenses. Audio was mastered on quarter inch reel-to-reel magnetic tape, using the industry standard stereo Nagra IVs-tc recorder, modified for center-track timecode.

“Shooting on film was a work of art.” Says filmmaker Robert Lundahl. “Certainly editing on a flatbed was a work of art. It helps you see the process differently. It makes a different kind of film.”

Unconquering was one of the last productions to utilize the celluloid/acetate motion picture film format, and one of the last films to be printed at San Francisco’s historic Monaco Labs. “It was a statement,” says Filmmaker, Robert Lundahl.

Motion picture film began to be used commonly in the teens, just at the time the dams were built. One of the customers of the power from the dams was Rayonier Mill. Rayonier, in addition to making celluloid compounds for table tennis balls and guitar picks, made materials for movie films, thus helping to launch one of the defining industries of the 20th century. As the era ended, symbolized by the removal of the Elwha River dams, so did the era end for motion picture film.

The Film

Washington’s Elwha was known to produce the largest salmon in the lower 48 states. The Elwha Kings were the stuff of fishing legend, Chinook salmon weighed in at up to 100 lbs.

This legendary river was dammed in 1908 and again in 1926, in one of the first examples of non-local capital arriving into frontier environments for industrial based energy development.

Seattle Times writer, Lynda Mapes described Unconquering the Last Frontier as “The history of the entire Pacific Northwest.” It is, in a fundamental sense. When the Elwha Dam was built, the State of Washington had a law on the books, requiring that all dams must be built with fish ladders. But the Elwha River did not have fish ladders. None were possible, given the construction. The dam hung from steep canyon walls, leaving no easy access for spawning anadromous fish to reach their destination far upstream, once construction was complete. The prime spawning beds , home to their prehistoric ancestors, were no longer accessible.

The eventual interpretation of the legal remedy was to build a hatchery, done in lieu of a having the legally mandated fish ladders. Thus the Elwha set the unsustainable precedent of the hatchery system in the Pacific Northwest, which in turn, led to the construction of more dams and the subsequent devastation of even more fish runs. In that the hatchery on the Elwha was not successful, the trend led to even greater loss of natural resources.

Salmon runs, having uniquely evolved to match their specific spawning milieus, were choked to extinction by the loss of prime spawning habitat.

The Lower Elwha Klallam Indians made this river their home.

The watershed provided the basis for their sustenance and psychological well-being, providing food sources and offering spiritually important sacred sites. And then, through the Devil’s bargain, the salmon could no longer pass upstream of the dams. Their future was damned. Runs of world class fish were subsequently devastated, the resource utterly ruined in a series of mass die-offs.

They (salmon carcasses) were laid up all over the riverbank.” –Rachel Hagaman, Economic Director, Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe.

The people faced a similar plight. After their ranks had been decimated by smallpox and other European diseases, the Indian people were indiscriminately persecuted by the arriving settlers. They were forced to abide by laws that were unfair and even genocidal to them, such as being forbidden to fish in their usual and accustomed grounds. If an Indian were to be caught fishing, they could be taken to jail, starvation conditions aside.

Documentary filmmaker Robert Lundahl embarked on a decade-long journey in 1993, to tell the story of the Lower Elwha people and the river which had sustained them. His picture, released to theaters in the San Francisco Bay Area and across the Northwest in 2000, is the only film to address the historic trauma befalling the Native people.

This is important because, arguably, the history of events on the Elwha has been subject to political interpretations to this day. Many which marginalize Native people and deny their voice, jeopardizing their cultural and physical survival. UNDRIP, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples sets agreed upon standards which “affirm that indigenous peoples are equal to all other peoples, while recognizing the right of all peoples to be different, to consider themselves different, and to be respected as such.” The film represents the clear-eyed understanding, on the ground, that UNDRIP requires.

Future

As the salmon move upstream to spawn and die, the marine-derived nutrients in their bodies will be returned to the forest along 113 km of wild river. Several hundred thousand salmon will eventually repopulate the river annually, bringing a huge quantity of nutrients that will permeate throughout the ecosystem. Because all of the water above the upper dam is in the Olympic National Park, these ecological changes will be available for long-term study, without the confounding influences of human disturbance that are common in virtually all other river restoration projects. Thus, the Elwha dams, by far the largest ever to be removed, constitute a unique opportunity to study the recovery of a riparian ecosystem, with profound implications for the value of dam removal elsewhere as a general conservation strategy (The University of Washington).

The removal of the concrete structures of the Elwha Dams began in 2012, initiating a profoundly new era in conservation management. Never before had dams this large been removed. Never before had an ecosystem been ameliorated like this, restoring complex interactions and allowing synergistic effects to resume flourishing naturally once again.

Our obligation to the future includes making this watershed picture available to new audiences, as an anthem for restoring balance to the world and a bold idea for preserving hope. When Winona LaDuke invites us to “recover the sacred,” the well known Native American organizer is requesting far more than the rescue of ancient bones and beaded headbands from museums. For LaDuke, only the power to define what is sacred—and access it—will enable Native American communities to remember who they are and fashion their future.

In the healing of historical trauma, the restoration plays a significant part in returning dignity to the indigenous cohort of our nation’s population, an important social aspect necessary for our growth and development as a modern group of people.

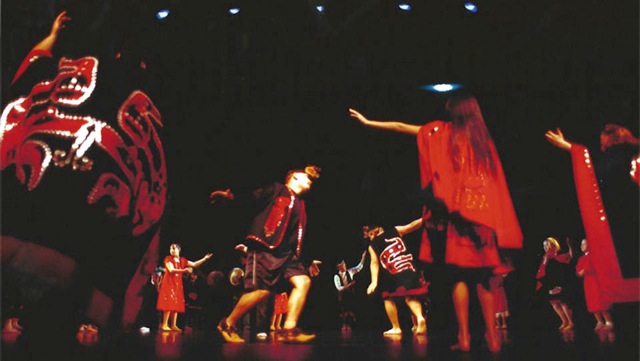

The Changer, or Transformer is a supernatural force or being capable of transforming one species into another, a bear into a deer, or a wolf.

It is not enough to just remove the concrete superstructure from a river, if what is left behind is mere drainage. It’s not enough to just reintroduce salmon populations to a river. We must support the historical narrative, and acknowledge the emotions of a people as we witness the return of a way of life that had once been taken from them. To understand the essence of the Elwha Story, understanding the Klallam and their culture is essential. To understand what the settlers and the dams took away is to begin to understand what the river means to all of us. It is as close as we’ve gotten to redress and reconciliation, which is to say that environmental justice and stewardship are one in the same. The Elwha provides a tangible lesson on both, for the be benefit of people around the world to see and consider.

History

Unconquering the Last Frontier is a work of history. The film relies on original, first person accounts dating to the 1830s. The film is in use educationally by Harvard, Yale, Dartmouth, The University of Washington and other top universities. It has been publicly vetted and peer reviewed. Unconquering is in the collection of The Smithsonian/ National Museum of the American Indian.

Unconquering the Last Frontier clarifies the actions of the past through a rigorous examination of historical facts.

Unconquering examines the nature of energy development at that time, as events on the ground played out in context during the early years of the 20th century.

-The film reveals that Native Americans placed logs along the river to help manage flows and fisheries in the mid 1800s.

-That fisheries pressures were not new and the Territories of Oregon and Washington declared emergencies in the 1870’s as the fish were dangerously over harvested.

-The film examines whether the Elwha dams were built legally and whether the dams’ builder, Thomas Aldwell promised to build fish ladders as a condition of their construction.

-Unconquering the Last Frontier describes the relationship between the Elwha Dams and the hatchery system across the Northwest, as a precursor and precedent.

-Unconquering the Last Frontier examines the history as told by the Native people themselves, and their attitudes about it.

The Lesson Plan

It is of global importance, how the story of the restoration of the Elwha River and fisheries came into being be told. To this date, full ecosystem restoration at this scale has occurred only once. We are looking at the prime and only example of large scale remediation to the river ecosystem including the landscape, fisheries, culture, spirit and economy of a Pacific Northwest Region. In restoring the Elwha, we have a pattern for other endeavors and a seed for success. It can be done.

According to the Center for Biological Diversity, “Ecological restoration is the process of reclaiming habitat and ecosystem functions by restoring the lands and waters on which plants and animals depend. Restoration is a corrective step that involves eliminating or modifying causes of ecological degradation and re-establishing the natural processes — like natural fires, floods, or predator-prey relationships — that sustain and renew ecosystems over time.”

1. It is important to introduce the concept that ecological restoration is worthy of consideration in addressing landscape level issues having to do with water, toxic substances, ecosystem health and the health of people. With regard to the public/private process to restore the Salton Sea, reintroduction of water to the system allows ecosystems to be supported and to become more fecund, making for a cleaner and healthier environment and thus stabilizing the region.

The removal of water from the southern San Joaquin Valley similarly sees soils become salted, non-productive, and subject to conversion from agriculture to energy production (fracking) and other industries. Toxic compounds compile at specific locations, affecting wildlife and avian species and human beings, through blowing dust and particulates. The lesson of the Elwha is “Let nature run its course.”

Unconquering the Last Frontier shows the debate, framing the story of a waterfront mill town as it ponders its future while confronting its past.

2. Show that what happened on the Elwha, for better and for worse, as the result of decisions made by people who affected the outcome. The decision to build the Lower Elwha Dam, which cut off the fishery 4.3 miles upriver, was a decision based on engineering and cost for the specific purpose of generating power at that location. It is important to realize that a myriad of choices were available to the solution of generating power. The location on the Elwha, as a specific site to do that, had an enormous down side.

What some people did not know then about the fragility of the resource became, over time, the top consideration from a policy and cost perspective across the entire Pacific Northwest region. It would be fair to say, in addition to questions about legality, morality, and philosophy, that questions still remain about the engineering decisions made.

Too often our society solves a problem having to do with financial benefits accruing. Yet, had the “engineering” solution been better focused on generating power at less cost and detriment overall, the solution might have been entirely different.

How we think about the context and consequencess of our actions is critical to their outcome. In this way, we begin to account for the likelihood of unintended result in the design/engineering process itself.

If an analysis of context and consequences was inadequate in the beginning, we may be assured we will eventually be looking at GIGO (Garbage In, Garbage Out). As simple as this idea sounds, we still are faced with the same scale of poor outcomes, made by decisions mandated by financial incentives, without weighing the true costs. We build solar generation plants in dry lake beds, atop prehistoric Native American ruins, and accept renewable energy installations that require burning fossil fuels- natural gas, to maintain output, making them not renewable at all.

Even today, these costly errors are still committed. We have not learned yet, despite a desperate need to embrace a more intelligent way of being on the planet without wrecking the ecology.

3. Connecting the dots via a side-by-side demonstration of the restored meander of the lower river with the reconstitution of the estuary, compared to then and now aerial photography, filmmaking, etc. Connect the dots by interviewing tribal members about the meaning of “recover the sacred.” Interviews with select individuals from the original film, including the filmmakers, round out the perspective related to the full spectrum of happenings stimulated by this bold and historic undertaking.