Originally Published in The ECOreport. By Robert Lundahl.

As a filmmaker I spent four years, beginning in July, 2010, investigating the impacts of large solar development on the deserts of my home state of California.

Solar development in the deserts of the Southwest was initiated as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which included $6 billion for loan guarantees, an amount that was far exceeded in actuality, over subsequent years.

In addition to loan guarantees, the ARRA created a grant program for business. A facility owner could choose to receive a one-time grant equal to 30 percent of the construction and installation costs for the facility. Eligible projects included anaerobic digesters, landfill gas, solar, and wind.

With 30% up-front in cash, the business risks of project development were substantially reduced and a “feeding frenzy” ensued. Speculative investors like Goldman Sachs applied for low cost leases on public lands and the queue, to be managed by the Bureau of Land Management, was long, with over 200 projects in Southern California alone.

“Who Are My People?” ©2014 Robert Lundahl

I had thought of the deserts of Southern California as a grand “backyard” to the polluted environs where I was raised, in Pasadena, Los Angeles County. The deserts provided “breathing room” for an emerging connected metropolis of Los Angeles, Orange and San Diego Counties, where population had grown exponentially.

With industrial development now threatening the more remote desert regions, I questioned whether and how such large scale development might be managed, and whether there would be anything left of the deserts which had stimulated my curiosity as an adult. The impacts included those to plants and animals, waters, soils and air quality, and to the American Indian cultures I had come to know, making two previous films.

The academic distance I had tried to maintain dissipated when I witnessed the destruction of ancient geoglyphs, giant earth works, made by earlier civilizations, which American Indians attribute to a connection with the Cosmos. These geoglyphs express an intricate set of inter-relationships between places, ancient art, and people, incorporating what scientists refer to as archeo-astronomy. We were destroying the work of their Gallileos in a mad rush to receive the cash grants. Billions were at stake and the world’s energy companies were at the door.

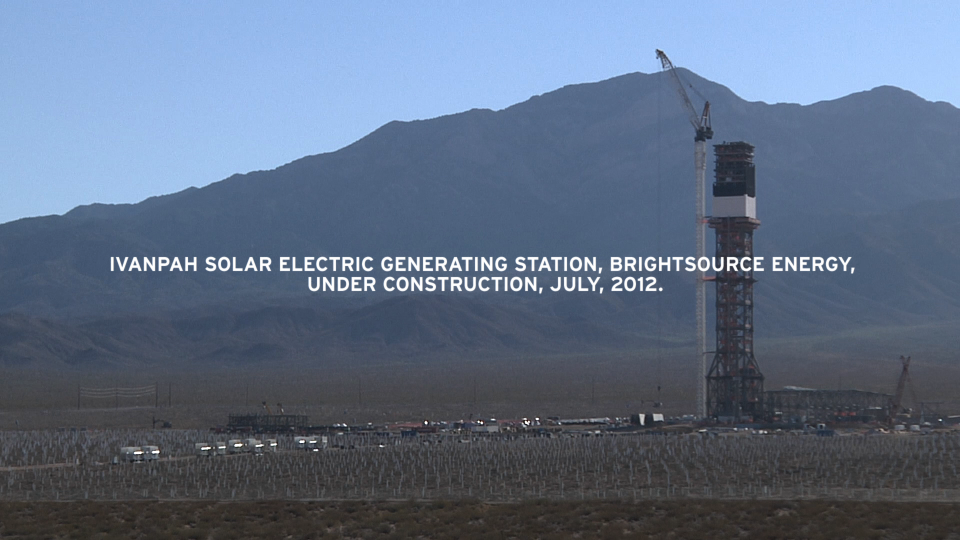

Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System. “Who Are My People?” ©2014 Robert Lundahl

The first major project was built, at Ivanpah, and brought on line in 2014. It is a name meaning White Clay Waters, in the Chemehuevi language, in a region known as the best habitat available for the Desert Tortoise, a “Protected Species.” 5 square miles were graded. Down the road at another site, the Genesis project had been started. There, Kit Fox were decimated by distemper, a scourge some say was attributed to the urine of construction workers’ dogs.

They say the road to hell is paved with good intentions, and while mitigating climate change, or doing our part as a nation is a good intention, it remains an unconvincing argument that remotely sited industrial solar and wind is the answer, given that Germany has added 500 MW of renewable energy a month to their energy “portfolio” using rooftops.

There were victories of a sort. A lawsuit had stopped a large facility in Imperial County. And the so called “Largest Solar Project in the World,” Blythe Solar, was abandoned in 2011 when opposition exposed poor construction practices and violations as the applicant, Solar Millennium, raced to build infrastructure that would have allowed cash grants to become available. A similar project was mothballed at Rio Mesa in 2013, near beds of Mammoth fossils — and at Hidden Hills in Nevada, where California state anthropologists validated that Paiute cultural lands (The Paiute are a historically nomadic people) extended over the project. In a world where we as “civilized peoples” lament the destruction of the “Taliban Buddhas” and ancient Babylon destroyed by war, it is somewhat heartening to know our own American antiquities carry some weight for preservation, though not much. The California Energy Commission indicated 17,000 Indigenous “Sacred Sites” would be destroyed by energy development in the deserts.

This Place Matters. “Who Are My People?” ©2014 Robert Lundahl

After coming to grips with new levels of thoughtlessness and destruction, it was of no particular surprise that the Ivanpah project was revealed in the press in 2014 as “incinerating” the birds of the Pacific Flyway, the migratory pathway followed by hundreds of bird species that converge to the Salton Sea portal south into Mexico, Central and South America, From all over North America. Dead birds included endangered species like the resident Yuma Clapper Rail and iconic ones like Golden Eagles. Projects like Ivanpah have been labelled “Death Traps” because they look like lakes from above. Tired birds navigate down toward rest and water and become “streamers”, smoking projectiles hurtling to Earth.

The Palen project would be the worst. With two enormous towers capped by solar receivers projecting their “brilliance” over the Southeast corner of Joshua Tree National Park, the project had everything going for it. Not only would it destroy Native sacred sites and cultural resources, fry bird species, eliminate many square miles of habitat for plants and animals, it would negatively impact tourism to the National Park and the economic heath of communities like Joshua Tree, at the Park’s entrance. The project was so bad it became one of the few that had been denied a permit by the CEC, California Energy Commission. But then, inexplicably, the applicant, BrightSource, was allowed to amend the application. A renewed project with one tower only and the possible inclusion of a second at a later date, plus an energy storage component to smooth out its power delivery to the grid, was offered conditional approval despite the unmitigable impacts. The project had been denied, then Dracula–like, it had surfaced from the grave and won half-hearted approval.

Prayer. “Who Are My People?” ©2014 Robert Lundahl

Numerous Indian tribes had delivered impassioned testimony against the project. Neither was the public happy, according to on-the-record comments. At the darkest hour, it seemed certain a slew of 16 penny framing nails would be hammered into a tiny coffin containing the carcasses of little burned Wrens and Warblers, Tortoise and Kit Fox, and the dreams of Native Americans, long the victims of genocide, physical and cultural, following California’s Gold Rush, and the forced removal of their children to Indian Schools as late as the 1950’s.

California’s DRECP, or Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan, was instituted following the approval of BLM’s national plan for the Southwest. The DRECP, a joint effort of federal and state agencies, would allocate 22 million acres to “development ” and determine lands also to be “conserved.” The DRECP process had been the official channel for receiving the input of “stakeholder groups” including large environmental organizations like the Sierra Club. It was released publicly in draft form, at a photo op beneath the enormous rotating blades of a giant field of Wind Turbines outside Palm Springs last week. Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell stood positioned heroically against a dust-blown desert sky. Secretary Jewell joyfully extolled the virtues of renewable energy development in the desert on a scale the world had never known.

74 year old grandmother, Pat Flanagan, is a Board Member of the Morongo Basin Conservation Association. In 1983, she was the field biologist that monitored the prototype Solar One facility at Daggett. Pat had spent the previous weeks rising at dawn, correlating data from thousands of pages of CEC, California Energy Commission and BLM, Bureau of Land Management documents. She had used a simple search tool across myriads of .pdfs, to track the usage of terminology like “solar receiver” as it applied to the Palen project and its permitting.

Oddities emerged. The Palen Project was described by the CEC as being a 750′ Tower with a 130 ft. receiver “atop,” yet the BLM docs described a 68 foot “solar receiver.” Did “atop” mean “contained within the height of” or “in addition to”? The CEC and the BLM were not in sync and the language was not clear. As both state and federal agencies were involved, this would seem to invalidate the Palen Project permit. To properly communicate, the BLM draft and the CEC documents would need to be rewritten (reanalyzed) and submitted again to the public for review. If challenged in court, this would become a time consuming process, and time was running out for applicant BrightSource.

Battling Goliath was a disappointment. Goliath was not a very good writer, nor a thorough editor. Goliath couldn’t get his facts straight.

Pat completed her report. She uploaded it to the CEC website at 9:01 am on Friday the 26th. Then at 3:05 pm, out of the blue, in an action that without doubt shocked the world’s energy industries and financial institutions, BrightSource withdrew the project. It was over. Goliath threw in the towel.

The article in the Palm Springs Desert Sun reads: “BrightSource senior vice president Joe Desmond said the developers chose to withdraw their application in part because the project was unlikely to be completed by December 2016, meaning it wouldn’t qualify for a 30 percent investment tax credit that expires at the end of that year.”

I suppose that is the logical conclusion of a value set that places money above people. Goliath had wanted it too easy. I expected a better fight.

###

©2014, All Rights Reserved. Reprint By Permission Only.