Category Archives: blog

https://intercontinentalcry.org/people-documentary-film-premiere-canada/

“Who Are My People?” Documentary Film to Premiere in Canada

“Who Are My People?” the first film to investigate the dark side of green energy development in California will premiere in Canada’s Manson’s Hall, Cortes Island, 7:00 pm. February 6, 2015.

Mojave Elder Victor Van Fleet leads tribal Bird Singers in songs to protest energy development destroying lands sacred to Native American peoples in the California deserts. Giant geoglyphs, visible from space, are endangered by energy development in the California deserts; these energy developments are touted as “Green” by corporate and government backers, though the technologies are considered by many to be anything but. ©2015 Robert Lundahl, Robert Lundahl & Associates. From “Who Are My People?” documentary film.

Article 8 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states, Indigenous Peoples and individuals have the right not to be subjected to forced assimilation or destruction of their culture. But in the US and Canada, as well as many other nations, what occurs in practice, on the ground, does not always conform to these ideals.

“Who Are My People?” from documentary filmmaker/investigative journalist Robert Lundahl, explores the destruction of Native American cultural sites, in-tact desert ecosystems, and biodiversity values, in the rush to profit from “Green Energy.”

Even in the United States, which considers itself among the most advanced or progressive democracies, indigenous communities are subjected to the destruction of their cultures, while those who should know better look the other way.

In the quest to develop green energy in the deserts of California, for example, some say environmentalists and “Green Energy” supporters lack an understanding of the consequences of their actions and choices. Global energy firms like NextEra, Brightsource, and Iberdrola participate in what some have called a “Gold Rush” for the new “Green Energy” profits.

This is the subject of Emmy® Award winning filmmaker Robert Lundahl’s new documentary, “Who Are My People?”. “It may seem inconceivable to those on the left,” he says, “That their own ambitions could be aligned in the historical context with “Indian fighters,” John C. Fremont and General George Armstrong Custer, who suffered defeat at the Little Big Horn.”

At risk are a fantastic array of Native American cultural sites, now facing the bulldozer. The Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT) have litigated the issue, filing a complaint on December 4, 2014. “The religion and culture of CRIT’s members are strongly connected to the physical environment of the area, including the ancient trails, petroglyphs, grindstones, hammerstones, and other cultural resources known to exist there,” the tribes allege in the complaint, filed on December 4 in U.S. District Court Central Division of California, Eastern Division. “The removal or destruction of these artifacts and the development of the Project as planned will cause CRIT, its government, and its members irreparable harm.”

Lundahl, a long time environmentalist, himself, explains, “There is a lack of awareness on behalf of the environmental community of indigenous rights.” Solar Power expert Bill Powers P.E. explains in the film, “Isn’t it great that the big environmental groups and the utilities can agree on strategy… It just happens to be a very high impact strategy.”

Mainstream environmental groups like the Sierra Club and NRDC have supported large solar despite environmental and cultural degradation.

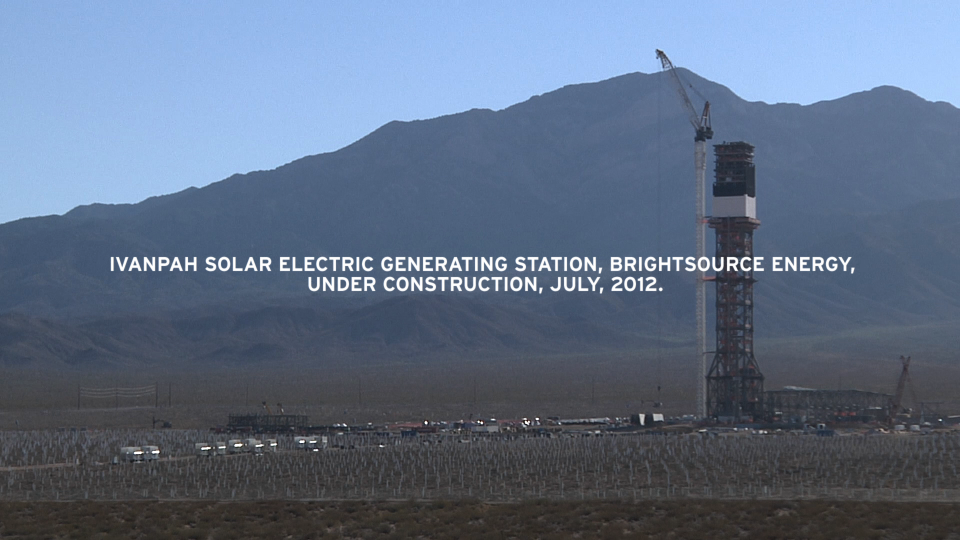

The issue has come to a head in the California deserts where the ARRA stimulus program loan guarantees and cash grants have provided up-front capital for developers in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Companies like Solar Millennium, a large solar provider, now bankrupt, and Brightsource, whose string of failures to permit large solar projects, have contributed to what some perceive as an industry “black eye.”

The industry as a whole has been criticized for Pacific Flyway avian mortality from projects like Brightsource/NRG/Google’s Ivanpah, and for the deaths of perhaps thousands of protected desert tortoise from the grading and development of project lands totaling up to 5 square miles each, Ivanpah and First Solar’s Silver State included. The California Energy Commission identified the likely destruction of over 17,000 cultural sites, opposed by the Native elders in the film.

Lundahl’s film, “Who Are My People?” includes gorgeous aerial photography and haunting descriptions of over 20 large geoglyphs, now endangered. They form a mythic landscape, one from from another time or dimension of experience, located along the Colorado River. Indigenous elders, Ron Van Fleet (Mojave), Phil Smith (Chemehuevi), Alfredo Figueroa (Chemehuevi), and Preston Arrow-weed (Quechan), tell the story.

The 2/6/15 screening is sponsored by CKTZ Radio 89.5 fm and The ECOReport.

###

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Robert Lundahl & Associates

Documentary Filmmaking

Public Policy Communications

415.205.3481

CLIMATE OF DESPAIR: ENERGY COMPANIES PURSUE PROFITS AT THE EXPENSE OF INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES WORLDWIDE

Communities North and South Awaken to Shared Struggle, Unpleasant Truths

Commentary By Robert Lundahl

Might makes right so the saying goes. Arguably amid the power dynamics of our systems and civilizations there is no greater power than that in the hands of energy producers on a planet choking in the aftermath of a fossil fuel consumption binge.

As world leaders meet in the elite confines of Davos, Switzerland for the 2015 World Economic Forum, whose topic is, predictably, Climate Change, many a writer might be tempted to ingest arsenic rather than parse the details of new climate strategies or rehash failed attempts at taking action. Amid this climate of despair we take insights where we can find them, and two articles appearing yesterday in the Guardian provide a clear focus on systemic failure and institutionalized ignorance.

As world leaders meet in the elite confines of Davos, Switzerland for the 2015 World Economic Forum, whose topic is, predictably, Climate Change, many a writer might be tempted to ingest arsenic rather than parse the details of new climate strategies or rehash failed attempts at taking action. Amid this climate of despair we take insights where we can find them, and two articles appearing yesterday in the Guardian provide a clear focus on systemic failure and institutionalized ignorance.

“It is profitable to let the world go to hell” tells the story of Jørgen Randers, who back in 1972 co-authored the seminal work Limits to Growth, which “highlighted the devastating impacts of exponential economic and population growth on a planet with finite resources.”

“The capitalist system does not help,” says Randers. “Capitalism is carefully designed to allocate capital to the most profitable projects. And this is exactly what we don’t need today.” “We need investments into more expensive wind and solar power, not into cheap coal and gas. The capitalistic market won’t do this on its own. It needs different frame conditions – alternative prices or new regulation.”

In other words, Randers suggests, despite the interest of progressive companies in promoting and financing renewable implementations that are constructive and economically positive, the overall inclinations of the markets are the reverse, procuring the cheapest energy at the cheapest price, plunging society into a downward spiral of pollution and environmental ravagement. When it comes to more regulation or higher taxes, Randers says voters tend to revolt and, as a result, politicians will continue to refuse to take courageous steps for fear of being thrown out of office.Thus systemic impediments to cheaper, greener energy will remain the norm for some kind of future time frame. With sea levels predicted to rise over the next 30 years 23-28 feet, this does not bode well for strategies of climate change mitigation.

Al Gore’s: “Oil companies use our atmosphere as an open sewer” continues the shock and awe at the status quo of the past 100 years. “It’s not possible to listen to petroleum industry executives defending their reckless extraction of oil without feeling that we are living in an age of madness,” he says, despite the fact that Gore family oil interests in Occidental Petroleum were harshly criticized during the 2000 election. The article continues that Gore, despite being perceived as a climate change moderate, thinks all the world’s hydrocarbons will continue to be burned until the end of the century.

In the article, Gore purportedly acknowledges that the burning of all reserves would almost certainly lead to temperature rises of up to 4C, and to that he argues the best way forward is to focus on limiting the damage through such technologies as carbon capture and storage, technologies which are unproven. Such blind obeyance to the scientific dogma that technologies will solve unsolvable problems before they become even more unsolvable is disingenuous drivel following a century during which this thinking has been stripped of any validity one hundred times over. When, might we ask, does science step in and save us from ourselves if it has not already? Gore’s future facing predictions conveniently justify, excuse, and paper over his family’s past-facing investments and actions in a “greed to green” cover up of epic cognitive dissonance.In light of such circular head spins of logic that are accepted as truths by the operational mindset of planet Earth’s minders and executives, let’s be truthful in the analysis that the cheapest energy at the cheapest price is located on land that can be obtained with the least opposition. Canada’s tar sands fit this criteria. Located in Northern Alberta, these energy resources are home to Indian Nations that for the most part of the last century practiced substance living. The same might be true for those indigenous communities at the output end of pipelines at shipping ports on the Pacific where peoples have survived depressions eating salmon and potatoes. Capital resources for legal defense and federal lobbying have not traditionally been part of per capita output of these areas. So today these communities began opposition to such large infrastructure projects affecting their lands from an enormously disadvantaged position.

From Northern Alberta, to California’s Mojave desert, the forested river valleys of Xingu in Brasil, and the Andean homelands of the Achuar in Peru, the Ogoni Delta of Nigeria, energy companies have willfully left a toxic trail of the most noxious pollution, destruction of lands and food sources and effective genocidal strangulation of cultures in their wake. According to Gore and Randers, we should not expect this pattern of abuse to come to a halt any time soon.

In the case of Al Gore’s Occidental Petroleum, a relevation of sorts, however, was gained.

Oxy’s environmental practices in Peru’s Corrientes River Basin, where the Achuar live, were extensively documented in the 2007 report, A Legacy of Harm: Occidental Petroleum in Indigenous Territory in the Peruvian Amazon, which ERI co-authored with Racimos de Ungurahui and Amazon Watch. The report found that Oxy’s contamination of the Achuar’s pristine rainforest environment has led to an epidemic of heavy metal poisoning, include lead and cadmium poisoning, among the Achuar. Other main findings of the report include: • Oxy dumped over nine billion barrels of “formation waters,” a toxic oil byproduct, directly into rivers and streams used by the Achuar for drinking, bathing, washing, and fishing – an average of 850,000 barrels per day.

• Oxy used earthen pits, prohibited by U.S. standards, to store drilling fluids, crude oil, and crude by-products. These pits, dug directly into the ground, were open, unlined, and routinely overflowed onto the ground and into surface waters, leaching into the surrounding soil and groundwater.

• Oxy’s inadequate infrastructure and poor maintenance led to numerous oil spills directly into the environment.

• Oxy violated Peru’s General Water Law and General Health Law, as well as environmental statutes meant to be applied in the hydrocarbon sector.

Until Gore comes clean about the systemic abuse Oxy perpetrated in Peru, his claims to expertise in Climate Change punditry carry no weight. The claim that technology advancements to come will be successful in mitigating bad behavior already perpetrated, is against all remnants of common sense.

###

CANADIAN REVIEWER SEES PARALLEL BETWEEN “WHO ARE MY PEOPLE?” FILM AND BC HYDRO “FIRST NATIONS” FIGHT

1/20/15

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Robert Lundahl & Associates

Documentary Filmmaking

Public Policy Communications

415.205.3481

CANADIAN REVIEWER SEES PARALLEL BETWEEN “WHO ARE MY PEOPLE?” FILM AND BC HYDRO “FIRST NATIONS” FIGHT

“Aboriginal Values, Beliefs, Title And Treaties Trampled,” Says Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs vice-president Chief Bob Chamberlin.

In advance of the premiere of Robert Lundahl’s Documentary “Who Are My People?” in Canada (2/6/15 Mansons Hall, Cortes Island, 7:00 pm) https://www.theecoreport.com/the-canadian-debut-of-who-are-my-people/, Peace Valley Environment Association Coordinator Andrea Morison made the connection between the development of utility scale solar in the deserts of California and BC Hydro’s Site “C” project at Peace River, British Columbia.

In British Columbia, a 52-mile stretch of northeastern B.C.’s Peace River valley is planned to be dammed and submerged—an area the size of Canada’s capital, Ottawa—a valley that is habitat for ungulate species including moose, elk and deer, as well as wolves, and which serves as a vital hunting, fishing and trapping ground for First Nations. The activities are protected under Treaty 8, which covers three provinces and a landmass twice the size of California.

In California, according to “Who Are My People?”, Robert Lundahl’s latest documentary, Indigenous tribes and cultural groups oppose “Fast-Tracking” of energy developments, some of which are to be constructed or are being constructed on, around and near vast Native American cultural resources in the area. Biodiversity values are also endangered according to Dr. James Andre, Director, Sweeney Granite Mountains Desert Research Institute, UC Riverside.

Andrea Morison, MA is Communications Consultant and Facilitator to Peace Valley Environment Association: “There are definitely many parallels between the issues the people of SW CA faced in their battle against large solar and our battle with Site C. Very similar in many, many ways!” Morison continues, “I really liked the fact that the film focuses on the human impacts in terms of culture, and that there was very little on the technical side of things associated with solar installations. People care about people – there is no need to inundate us with technogarble – just connect people to people.

Andrea Morison, MA is Communications Consultant and Facilitator to Peace Valley Environment Association: “There are definitely many parallels between the issues the people of SW CA faced in their battle against large solar and our battle with Site C. Very similar in many, many ways!” Morison continues, “I really liked the fact that the film focuses on the human impacts in terms of culture, and that there was very little on the technical side of things associated with solar installations. People care about people – there is no need to inundate us with technogarble – just connect people to people.

Indigenous people and rural communities suffer in the shadow of energy development on both sides of the border. From Indian Country Media Network: The Site C dam has drummed up controversy since the 1980s, when the provincial B.C. Utilities Commission shelved the decades-old proposal, ruling it was not needed. After the province resurrected the idea in the mid-2000s, the government declined to send it back to the commission, instead holding a series of reviews that concluded in October 2014 that impacts on First Nations could not be mitigated.

Solar energy projects in California will likely impact over 17,000 Native American sacred sites according to the California Energy Commission’s Beverly Bastian. Indian Country Today: The Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT) have filed suit to get approval rescinded for the Blythe Solar project in the Mojave Desert, saying the 4,000-acre project will destroy huge swathes of sacred sites. http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/12/10/colorado-river-tribes-sue-interior-blm-stop-blythe-solar-project-15821

The Mojave, Chemehuevi, Hopi and Navajo tribes’ reservation is just a few miles northeast of the site, putting the project firmly within their ancestral homelands, the complaint alleges. They have sued under the National Historic Preservation Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, the Federal Land Policy Management Act, and the Administrative Procedure Act, according to Courthouse News.

Morison knows her business. She is former Sr. Aboriginal Program Specialist BC Oil and Gas Commission, and Former Aboriginal Liaison Officer BC Ministry of Forests. “Given my focus on energy issues for the last 4 years, it doesn’t surprise me that there are detrimental impacts associated with this type of energy infrastructure. I really don’t know alot about the solar option, but never thought it was a ‘perfect’ answer. I had heard that there are issues with the mining practises associated with the extraction of materials used to make panels. It seems, according to a few of the people in the film, that solar may have a place on rooftops and in parking lots. I imagine, just like many alternative energy technologies, there are a wide range of designs which can be built to accommodate various needs and locations and minimize impacts.”

The Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs promised to stand with Treaty 8 bands “to ensure that BC Hydro’s Site “C” does not proceed, according to a statement provided Indian Country Today. The Peace River was already dammed twice in previous decades, the Union stated, and the harm to First Nations has been cumulative ever since.

“Approval of this projected signals to First Nations across B.C. that their values, beliefs, title, aboriginal rights and treaty rights will essentially be trampled upon, cast aside and disregarded whenever government deems a project economically important and significant,” argued UBCIC vice-president Chief Bob Chamberlin.

A First Nation whose treaty lands will be flooded when the $8.8-billion Site C dam is completed in a decade is vowing to step up its ongoing legal battle against the project after it was approved by the province last week.

West Moberly First Nation is already embroiled in several court cases seeking a judicial review against the 1,100-megawatt hydroelectric project, slated to start construction next July. Now the band’s chief says that in addition to the five existing lawsuits—and a sixth in the works—he intends to file for injunctions to block the thousands of permits that BC Hydro needs to start work.

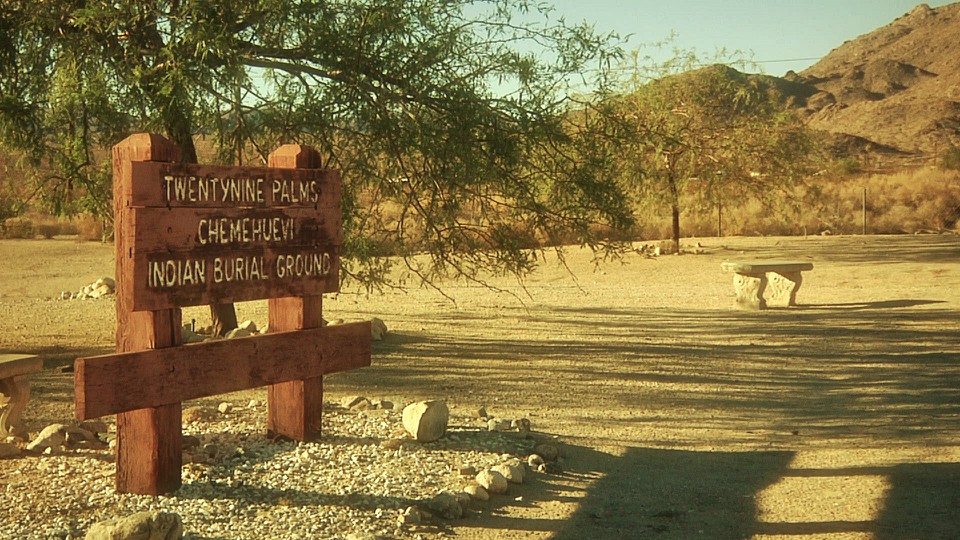

The Oasis of Mara, 29 Palms, California, from “Who Are My People?” Documentary Film By Robert Lundahl ©2015

Robert Lundahl

Principal

Robert Lundahl & Associates

robert@studio-rla.com

Skype: robertundahlfilms

415.205.3481–Direct

https://planet-rla.com

“Who Are My People?” A Conversation Between Roy Hales, Editor, TheECOReport.com and Andrea Morison

Andrea Morison:

There are definitely many parallels between the issues the people of SW CA faced in their battle against large solar and our battle with Site C (http://www.savebcfromsitec.ca/). Very similar in many, many ways!

Roy Hales:

What did you think of the film, “Who Are My People?” In terms of quality & content.

Andrea Morison:

I thought the quality was great. I loved the old footage and photos – resonates with me and I believe will also resonate with a large segment of the population to which this film will appeal.

I also loved the music – so much so that I actually wrote down the artists and plan to look them up – the first time I have ever done that from film credits in my life!

I really liked the fact that the film focuses on the human impacts in terms of culture, and that there was very little on the technical side of things associated with solar installations. People care about people – there is no need to inundate us with technogarble – just connect people to people.

There’s no doubt that those geoglyphs are extremely interesting – so rare and make us extremely curious – great attention grabber. Different than the usual ecosystem-type and cultural concerns.

Roy Hales

Does anything surprise you? What about the fact this is “green” technology?

Andrea Morison:

Given my focus on energy issues for the last 4 years, it doesn’t surprise me that there are detrimental impacts associated with this type of energy infrastructure. I really don’t know alot about the solar option, but never thought it was a ‘perfect’ answer. I had heard that there are issues with the mining practises associated with the extraction of materials used to make panels. It seems, according to a few of the people in the film, that solar may have a place on rooftops and in parking lots. I imagine, just like many alternative energy technologies, there are a wide range of designs which can be built to accommodate various needs and locations and minimize impacts.

Andrea Morison, MA is Communications Consultant and Facilitator to Peace Valley Environment Association. Fort St. John, British Columbia, Canada

The Oasis of Mara, 29 Palms, California, from “Who Are My People?” Documentary Film By Robert Lundahl ©2015

Originally Published in the ECOReport

Andrea Morison, MA is Coordinator, Peace Valley Environment Association, Fort St. John, BC, Canada

“Who Are My People?” a documentary film by Robert Lundahl, will leave you thinking that the English language is at a deficit when it comes to allowing one to accurately describe, in a single word, what we now, inaccurately label ‘green’ and ‘renewable’ energy.

Lundahl brings you to the southwestern California desert, a seemingly perfect location for the world’s largest solar installations.

Afterall, what could be wrong with capturing all that California sunshine on a blank desert landscape?

Plenty, it turns out. In fact these massive solar installations take up huge quantities of land and on this particular landscape lies some of the of the world’s greatest, unsolved mysteries!

But apparently, ‘green’ and ‘renewable’ energy trumps those mysteries of the land, at least according to the California government who gleefully promotes the projects.

It occurs to you that corporate and government entities conveniently capitalize on the commonly embraced terms ‘green’ and ‘renewable’; they can’t believe how fortunate it is that our language presents such deficits that allow them to ‘foil’ the public so easily.

How many among us, have been led to believe that a ‘green’ and ‘renewable’ energy source such as solar is a ‘good’ thing? Who Are My People prompts us to think harder about how accurately these terms describe potential energy solutions; seek a better range of energy options that have truly minimal impacts…and, who knows, maybe we’ll come up with a few more words to add to the Oxford dictionary. See: http://whoaremypeople.com/

The Oasis of Mara, 29 Palms, California, from “Who Are My People?” Documentary Film By Robert Lundahl ©2015

1/15/15

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

TheECOreport.com

Contact:

Roy Hales

Email Editor Roy Hales

“WHO ARE MY PEOPLE?” DOCUMENTARY FILM TO PREMIERE IN CANADA. INTERVIEW WITH FILMMAKER ROBERT LUNDAHL NOW ON TheEcoReport.com https://soundcloud.com/the-ecoreport/the-canadian-debut-of-who-are-my-people.

“Who Are My People?” the first film to investigate the dark side of green energy development in California will premiere in Canada’s Manson’s Hall, Cortes Island, 7:00 pm. February 6, 2015.

Article 8 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states, “Indigenous peoples and individuals have the right not to be subjected to forced assimilation or destruction of their culture.” But in the US and Canada, as well as many other nations, what occurs in practice, on the ground, does not always conform to these ideals.

“Who Are My People?” from documentary filmmaker/investigative journalist Robert Lundahl, explores the destruction of Native American cultural sites, in-tact desert ecosystems, and biodiversity values, in the rush to profit from “Green Energy.”

Even in the United States, which considers itself among the most advanced or progressive democracies, indigenous communities are subjected to the destruction of their cultures, while those who should know better look the other way.

In the quest to develop “Green Energy” in the deserts of California, for example, some say environmentalists and “Green Energy” supporters lack an understanding of the consequences of their actions and choices. Global energy firms like NextEra, Brightsource, and Iberdrola participate in what some have called a “Gold Rush” for the new “Green Energy” profits.

This is the subject of Emmy® Award winning filmmaker Robert Lundahl’s new documentary, “Who Are My People?”. “It may seem inconceivable to those on the left,” he says, “that their own ambitions could be aligned in the historical context with “Indian fighters,” John C. Fremont and General George Armstrong Custer, who suffered defeat at the Little Big Horn.”

At risk are a fantastic array of Native American cultural sites, now facing the bulldozer. The Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT) have litigated the issue, filing a complaint on December 4, 2014. (http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/12/10/colorado-river-tribes-sue-interior-blm-stop-blythe-solar-project-158213), “The religion and culture of CRIT’s members are strongly connected to the physical environment of the area, including the ancient trails, petroglyphs, grindstones, hammerstones, and other cultural resources known to exist there,” the tribes allege in the complaint, filed on December 4 in U.S. District Court Central Division of California, Eastern Division. “The removal or destruction of these artifacts and the development of the Project as planned will cause CRIT, its government, and its members irreparable harm.”

Lundahl, a long time environmentalist, himself, explains, “There is a lack of awareness on behalf of the environmental community of indigenous rights.” Solar Power expert Bill Powers P.E. explains in the film, “Isn’t it great that the big environmental groups and the utilities can agree on strategy… It just happens to be a very high impact strategy.”

Mainstream environmental groups like the Sierra Club and NRDC have supported large solar despite environmental and cultural degradation.

The issue has come to a head in the California deserts where the ARRA stimulus program loan guarantees and cash grants have provided up-front capital for developers in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Companies like Solar Millennium, a large solar provider, now bankrupt, and Brightsource, whose string of failures to permit large solar projects, have contributed to what some perceive as an industry “black eye.”

The industry as a whole has been criticized for Pacific Flyway avain mortality from projects like Brightsource/NRG/Google’s Ivanpah, and for the deaths of perhaps thousands of protected desert tortoise from the grading and development of project lands totaling up to 5 square miles each, Ivanpah and First Solar’s Silver State included. The California Energy Commission identified the likely destruction of over 17,000 cultural sites, opposed by the Native elders in the film.

Lundahl’s film, “Who Are My People?” includes gorgeous aerial photography and haunting descriptions of over 20 large geoglyphs, now endangered. They form a mythic landscape, one from from another time or dimension of experience, located along the Colorado River. Indigenous elders, Ron Van Fleet (Mojave), Phil Smith (Chemehuevi), Alfredo Figueroa (Chemehuevi), and Preston Arrow-weed (Quechan), tell the story.

The 2/6/15 screening is sponsored by CKTZ Radio 89.5 fm and The ECOReport.

Image Caption: Mojave Elder Victor Van Fleet leads tribal Bird Singers in songs to protest energy development destroying lands sacred to Native American peoples in the California deserts. Giant geoglyphs, visible from space, are endangered by energy development; these energy developments are touted as “Green” by corporate and government backers, though the technologies are considered by many to be anything but. ©2015 Robert Lundahl, Robert Lundahl & Associates. From “Who Are My People?” documentary film.

###

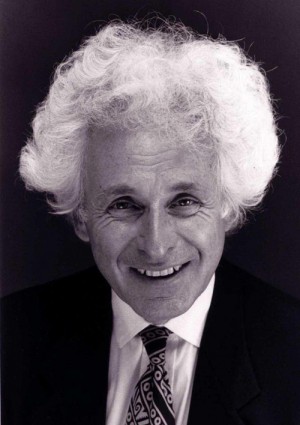

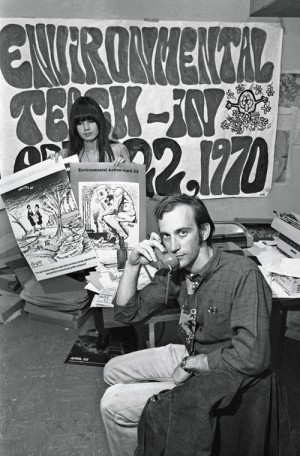

Excellence in communication had been the hallmark of the early environmental movement following the creation of the first Earth Day. David Brower, then head of the Sierra Club had worked with the Public Media Center, a non-profit ad agency founded by Herb Chao Gunther and Ad Exec turned Author Jerry Mander, who wrote “Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television,” “In the Absence of the Sacred,” and several other books.

After receiving his M.S., Mander worked in advertising for 15 years, including five as partner and president of Freeman, Mander & Gossage in San Francisco. Mander and Brower worked together, managing the Sierra Club’s advertising campaigns to prevent the construction of dams in the Grand Canyon, to establish Redwood National Park, and to stop the U.S. Supersonic Transport (SST) project.

Mander served as the executive director of the International Forum on Globalization, which he founded in 1994, until 2009 and continues on its staff as a Distinguished Fellow. He is also the program director for Mega-technology and Globalization at the Foundation for Deep Ecology.

Herb Chao Gunther wrote 10 Principles for Effective Advocacy Campaigns which is created from an awareness of American Realpolitik. The full explanation may be read here http://www.thegoodmancenter.com/resources/newsletters/10-principles-for-effective-advocacy-campaigns/

1. Communicate values.

“Americans need to hear there are certain things that are good or bad for the country,” Gunther asserts. “Absent that kind of moral clarity, people aren’t going to pay attention to the details.”

2. American political discourse is fundamentally oppositional.

People are more comfortable being against something than for it. Again, Gunther draws his most convincing examples from politics. Negative ratings for candidates didn’t exist 16 years ago. Today these ratings are routinely gathered by pollsters and closely scrutinized by the media.

3. The undecided in the middle determine the outcome of a given fight.

PMC’s work with the National Abortion Rights Action League reminds Gunther that principle #3 is alive and well today. When an issue polarizes as strongly as abortion, public interest groups should not waste time and resources trying to convert true believers at either end of the ideological spectrum. As Gunther told Planned Parenthood while planning a recent campaign, “Our fight is for the muddled middle.”

4. Americans want to be on the winning side. Based on this inclination, “undecideds” frequently choose the side that appears stronger.

“Americans don’t like to feel stupid, and going for the winner is a reflection that their self-esteem constantly has to be stroked and renewed.” As evidence, Gunther points to post-election polls which consistently show more voters claiming to have voted for the winner (as many as 15%, in fact ) than actually pulled the lever.

5. Make enemies, not friends. Identify the opposition and attack their motives.

“A fundamental tenet of democracy is accountability,” Gunther emphatically states, adding “Naming names is all about accountability.” Gunther proudly points to PMC’s campaign against the proposed theme park, “Disney’s America,” that featured an advertisement portraying CEO Michael Eisner as “The Man Who Would Change History.” Gunther believes the vilification of Eisner was critical in forcing Disney to cancel plans for the park, and he encourages public interest groups to employ a similar strategy. “CEO’s are confined to a statesman like role. This limits their ability to fire back. Don’t be afraid to attack!”

6. American mass culture is fundamentally alienating and disempowering.

“Most people don’t think they belong to this country in one way or another,” says Gunther. Several factors stoke these feelings of alienation: racial and ethnic divisiveness, class conflict, the sheer size of the country, and technology that leaps ahead faster than our wisdom to use it. Consequently, Gunther believes it’s more important than ever for public interest groups to educate, empower, and motivate their target audiences as part of their campaigns.

7. Target a few key audiences and strategize for social diffusion through opinion leaders, not by reaching the mass audience.

“When surveys say the majority of Americans feel they don’t count, why spend so much of your resources trying to talk to them?” Gunther firmly believes it’s better to have somebody else talk to them directly, so PMC’s ads are designed to find and educate that select group who will deliver the message for you. And exactly how many people are we talking about? “Nine times out of ten, you need to convince about a thousand people.”

8. Responsible extremism sets the agenda.

“What Rosa Parks did was a responsible extremist act in her time. Aside from the anarchists, what happened in Seattle around WTO was responsible extremism.” Given this definition, Gunther maintains principle #8 is still valid, even if it relies on the work of controversial or so-called “fringe” groups. “The reason that Sierra Club negotiated a settlement with a lumber company is because Earth First was doing what they do.”

9. Social consensus isn’t permanent and must continually be asserted and defended.

“I have to characterize citizenship in this country as a state of somnambulance.” Given a sleep-walking populace, Gunther warns public interest groups that the passage of a law or election of a candidate is not the end of the fight. David Brower, founder of Earth Island Institute, once said, “There are no victories in the environmental movement, only stays of execution.” Principle #9 extends this maxim to all public interest issues.

10. Strategic diversity is essential to the success of social movements.

“Biological diversity is nature’s strategy for survival,” Gunther says, “and we have to recognize the message for our movement.” When you put out a single message, he warns, you make it very easy for the other side to figure out how to respond and how to take you out. You also fail to recognize that you probably have to move several constituencies at once (e.g., the public, business leaders, politicians), and each constituency deserves its own highly-targeted message.

From the advocacy perspective, Environmental Communication is values driven, designed to persuade and engage, and differentiate itself through strong positioning. It targets opinion leaders at key “choke points” and utilizes media to achieve “social diffusion.” It also attacks weak points of opposing organizations though these organizations may be more powerful. As Chao Gunther points out “CEO’s are confined to a statesman like role. This limits their ability to fire back.”

In the interim years since Chao Gunther’s 10 points have been written, corporations and their legal and risk management departments, playing an increasingly important role, have become even more reactionary and backward facing — less capable of participating in a values driven conversation in any form. Values therefore become an even more significant element of differentiation because in shifting the debate away from tactical rhetoric and into authenticity and moral clarity, we engage on terms for which there is often no credible counter argument.

###

By Robert Lundahl

Mojave Indian Woman, Edward Curtis, 1903.

Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (NHPA) requires federal agencies to take into account the effects of their undertakings on historic properties.

The regulations also place major emphasis on consultation with Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations. Consultation with an Indian tribe must respect tribal sovereignty and the government-to-government relationship between the Federal Government and Indian tribes.

While Indian tribal sovereignty is partially limited as “domestic dependent nations,” so too is the sovereignty of the federal government and the individual states – each of which is limited by the other.

The people’s sovereignty underlies both the U.S. federal government and the States, but neither sovereignty is absolute and each operates within a system of parallel sovereignty.

The individual states, like the Indian tribes, do not print currency or conduct foreign affairs; and the individual states are constrained by federal authority under the U.S. Constitution and are bound by the Bill of Rights.

Viewed in this light, tribal sovereignty is yet another form of parallel sovereignty within the U.S. constitutional framework, constrained by but not subordinate to other sovereign entities.

Russ Busch, attorney representing the Elwha Klallam, indicated to this writer that Indian status which began as “Wards of the State” evolved as it was upheld by 130 court cases from the 1830s to the present day, within the concept of sovereignty – to full administration and rights to self determination as is practicable within the fundamental laws of the United States. It is a flexible and evolving status whose goal is to establish and support Tribes in achieving self determination to the fullest extent. That is the obligation of the United States to the tribes.

What government to government consultation looks like “on the ground” is another matter. Other case studies may be marginally useful as a precedent. In negotiations to end the Vietnam War for example, with three sovereign nations participating, diplomats spent months simply arguing over the shape of the negotiating table.

In the example of the United States seeking to develop the Mojave desert for energy, with historic properties and antiquities endangered, such negotiations are required by law with Indian sovereign governments. But it is doubtful in any case a government to government negotiation should look like this:

1. Sycuan Band of Kumeyaay Indians

10/6/11 – CDD staff called the Tribe’s staff regarding scheduling a meeting and was informed that an email had to be sent to Shiela Siva.

12/2/11 – CDD staff called the tribal office to schedule meeting.

1/24/12 – CDD staff received a call from Alan Hatcher regarding scheduling a meeting with the Council.

1/25/12 – CDD staff returned the call to Alan Hatcher regarding scheduling a meeting.

4/10/12 – CDD staff left a message for Jamie LaBrake offering GIS assistance to create a map for the DRECP.

1/4/13 – CDD staff left a message for Lisa Haws informing her of the DRECP Tribal Open Houses.

2. Torres Martinez Band of Cahuilla Indians

10/5/11 – CDD staff spoke with the Tribe’s staff regarding scheduling a meeting.

12/15/11 – CDD staff left a message for Matt Krystall requesting a meeting.

12/21/11 – CDD staff received a call from Matt Krystal requesting a meeting. He stated that he would call back regarding the Tribe’s availability.

1/4/12 – CDD staff left a message for Matt Krystall about scheduling meeting.

1/4/12 – CDD staff received a call from Matt Krystal about scheduling a meeting at the end of January. He stated that he would call back with an exact date.

3/23/12 – CDD staff called Matt Krystall regarding DRECP mapping.

4/12/12 – CDD staff called Ben Skoville offering GIS assistance to create a map for the DRECP, which he declined.

1/4/13 – CDD staff called Matt Krystall and informed him of the DRECP Tribal Open Houses

3. Santa Rosa Band of Cahuilla Indians

10/12/11 – CDD staff spoke with Steve Estrada regarding scheduling a meeting and was informed that a meeting with the Tribal Council was possible.

10/17/11 – CDD staff received a call from Steve Estrada regarding scheduling a meeting.

5/10/12 – CDD staff left a message for Steve Estrada offering on GIS assistance to create a map for the DRECP.

The three chronologies provided above are from Appendix V. of the DRECP, Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan, under “Tribal Consultation.” In accounts from contacts with over 40 Tribes the Bureau of Land Management, BLM, establishes a clear pattern of contact attempts with no actual consultation taking place.

On December 4, CRIT, the Colorado River Indian Tribes, brought suit against the Bureau of Land Management and the Department of the Interior. The account in Indian Country Today reads as follows:

“The Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT) have filed suit to get approval rescinded for the Blythe Solar project in the Mojave Desert, saying the 4,000-acre project will destroy huge swathes of sacred sites. The Mohave, Chemehuevi, Hopi and Navajo tribes’ reservation is just a few miles northeast of the site, putting the project firmly within their ancestral homelands, the complaint alleges. They have sued under the National Historic Preservation Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, the Federal Land Policy Management Act, and the Administrative Procedure Act, according to Courthouse News.” See full article here: http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/12/10/colorado-river-tribes-sue-interior-blm-stop-blythe-solar-project-158213

Not surprisingly, the account continues on to explain:

“The suit, filed against the U.S. Department of the Interior and the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM), alleges that the agencies did not adequately consult with tribes before approving the 1 billion project on August 1.”

“It accuses the government of failing to properly communicate with the tribe prior to approving the massive project,” reported another legal website, Law360.com.”

“BLM conducted no government-government consultation with CRIT prior to approval of the project,” the complaint says. “It then allowed the project developer to begin ground-disturbing activities before any cultural resource monitoring or treatment plans were in place.”

This writer, whose film, “Who Are My People?” debuted September 13 in Joshua Tree, California, spent 4 years researching similar circumstances and it remains the opinion of the subjects in the film, as expressed in it, and also via the legal complaint, La Cuna de Aztlán Sacred Sites Protection Circle v. BLM filed 12/28/10, which the film documents, that adequate consultation had not taken place in practice, in general.

This now appears validated by the DRECP Appendix V.

See: http://whoaremypeople.com

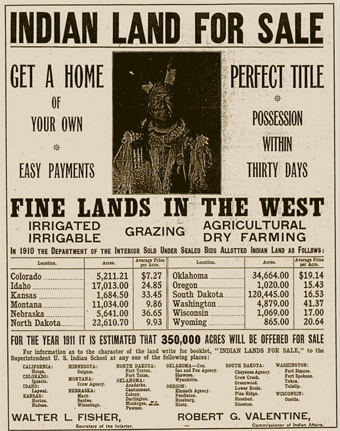

A failure to consult according to the law by government agencies not only places Indian culture in jeopardy but rolls back sovereignty to the conditions of the 1800’s when sailors disembarked to the land office to acquire Indian lands, then turned right around to sell them to developers.

“For nearly 300 years, white Americans, in our zeal to carve out a nation made to order, have dealt with the Indians on the erroneous, yet tragic assumption, the Indian was a dying race, to be liquidated. We took away their best lands, broke treaties, promises, tossed them the most nearly worthless scraps of a continent that had been wholly theirs. Report to the Secretary of the Interior, 1938.” (From Unconquering the Last Frontier, Film)

For more information about the films mentioned above visit: https://planet-rla.com/purchase/

By Robert Lundahl

Google’s investment at Ivanpah, the first of the large solar deployments, exemplifies the point that what is lacking from a public dialog on energy deployment and the DRECP, Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan, is a focus on consequences and feedback.

Grading 5 square miles of pristine desert tortoise habitat (a protected species), the plant is thought to have ended the existence of 1000 adult tortoise. BLM documentation includes loss of 1000 burrows as a separate incidence. Not only do these figures not “add up” but they also do not account for the death of juveniles — hard to find since they are underground –– and the loss of eggs. All told, one can only surmise that the impacts to the desert tortoise population at Ivanpah are in the multiple thousands. Given a BLM propensity toward undercounting impacts, it may be more that a simple counting suggests.

In addition, federal wildlife officials said Ivanpah might act as a “mega-trap” for other wildlife and avian species, with the bright light of the plant attracting insects, which in turn attract insect-eating birds that fly to their death in the intensely focused light rays.

Federal wildlife investigators who visited the BrightSource Energy plant last year and watched as birds burned and fell, reporting an average of one “streamer” every two minutes.

The investigators want the halt until the full extent of the deaths can be assessed. Estimates per year now range from a low of about a thousand by BrightSource to 28,000 by an expert for the Center for Biological Diversity.

These facets have been known for two years, but the large solar facility at Ivanpah, flagship of the ARRA stimulus program, whose investments were made through loan guarantees and cash grants, now relies on 40% burning of natural gas to fulfill contracts.

Google engineers describe their investments here: http://spectrum.ieee.org/energy/renewables/what-it-would-really-take-to-reverse-climate-change

“Google’s boldest energy move was an effort known as “RE>C,” which aimed to develop renewable energy sources that would generate electricity more cheaply than coal-fired power plants do. The company announced that Google would help promising technologies mature by investing in start-ups and conducting its own internal R&D. Its aspirational goal: to produce a gigawatt of renewable power more cheaply than a coal-fired plant could, and to achieve this in years, not decades.

Unfortunately, not every Google moon shot leaves Earth orbit. In 2011, the company decided that “RE>C” was not on track to meet its target and shut down the initiative. The two of us, who worked as engineers on the internal “RE C” projects, were then forced to reexamine our assumptions.”

Unfortunately, not every Google moon shot leaves Earth orbit. In 2011, the company decided that “RE>C” was not on track to meet its target and shut down the initiative. The two of us, who worked as engineers on the internal “RE C” projects, were then forced to reexamine our assumptions.”

These engineers mention that the “RE>C” failed to generate enough power in projections to offset coal, much less roll back climate change. This is an example of what is called “score-carding.” Adding and subtracting the line items but failing to address the consequences and feedbacks of a specific system. The reader is left to assume from the article that this was a well meaning “overshoot.” Something engineers have been tasked to “learn from.”

Was no one paying attention to the facts on the ground, the real world consequences and feedback? What about the social, cultural, environmental context? The article suggests an industry black eye.

Ross Koningstein & David Fork explain that unfortunately Google couldn’t solve “The Climate Problem” and the program was shut down. Their explanation admits no accountability for presumed capital losses due to inadequate power production, likely construction over-runs, a large solar industry of debunked Power Tower technologies exemplified by the failure to permit subsequent projects by co-owner Brightsource (Hidden Hills, Rio Mesa, and Palen). Nor does it acknowledge public and tribal opposition.

It comes as no surprise that several large environmental groups like NRDC and the Sierra Club, in supporting large solar, “flunked” the class. Ivanpah co-investor, NRG’s more acculturated and technology savvy CEO, David Crane, says despite these mega-projects, ultimately he sees no future for high-voltage transmission lines. “It’s idiotic to put panels in the desert and transmit electricity to cities.” Noting that there are 130 million wooden utility poles across the U.S., Crane wryly observed, “The 21st century economy should not be based on wooden poles.” Crane envisions a distributed solar future, whether it’s through rooftop or parking lot installations, observing that solar photovoltaic (PV) technology downsizes well.

Crane recently led NRG into a partnership with Nest https://nest.com/press/nest-partners-with-energy-companies/, a company that provides home energy-consumption solutions with an emphasis on elegant design. Crane sees a natural interplay between Nest’s technology and rooftop solar, into which NRG is increasingly expanding.

What do Halliburton, Georgia Pacific, and James Imhofe have in common with Rachel Carson, David Suzuki, and Bill McKibben? Environmental communication. The field is emerging and often misunderstood. It is assumed to be the domain of activists, but it comprises a wider spectrum of interests and messaging. It represents the conversations and meta-conversations about environmental issues, and our relationship to the biosphere and inter-species effects.

How these conversations take place, when they take place, how arguments are framed, and who participates in the conversation determines, to a large part, how effective an argument is.

The field has changed. Following 911, the 2008 economic recession, and the 2009 defeat of “cap and trade” bills to moderate carbon emissions, some sounded the “death knell” for the American Environmental Movement.

Victories that were forged in earlier times through a political process of concession and dealmaking, and sometimes pure momentum, began to unravel.

Nicholas Lemann writes in the New Yorker “When the Earth Moved, What happened to the environmental movement?”

“The story of the Environmental Defense Fund is illustrative. E.D.F. (is presented) as a raggedy group of amateur activists on Long Island, whose motto was “Sue the bastards!” It helped to get DDT banned in New York and elsewhere, and successfully pushed for water-safety standards nationwide. By the mid-eighties, though, it had become moribund, and a new president, Fred Krupp, then thirty years old, advocated an accommodationist direction for the movement, focussed on deal-making with big business and with Republicans. In the summer of 2006, Krupp and a few allies began assembling a coalition that met regularly at the offices of a professional mediation firm in Washington. He persuaded a number of major corporations with heavy carbon footprints, like Duke Energy, BP, and General Electric, to join. The coalition became an official organization called the U.S. Climate Action Partnership, funded primarily by a handful of major philanthropists and foundations. Shortly before President Obama’s Inauguration, USCAP released the fruit of its labors: a draft of the ill-fated carbon-emissions bill.”

Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger write in 2005, The death of environmentalism: Global warming politics in a post-environmental world,

“We believe that the environmental movement’s foundational concepts, its method for framing legislative proposals, and its very institutions are outmoded. Today environmentalism is just another special interest. Evidence for this can be found in its concepts, its proposals, and its reasoning. What stands out is how arbitrary environmental leaders are about what gets counted and what doesn’t as “environmental.” Most of the movement’s leading thinkers, funders and advocates do not question their most basic assumptions about who we are, what we stand for, and what it is that we should be doing.”

As Lemann continues he points a finger toward a different era, most unexpected for a generation or two of environmental communicators and policy makers.

“In the summer of 2009, Democrats in the House of Representatives, joined by a handful of Republicans, passed a bill based on the USCAP framework. It was fourteen hundred pages long. Almost immediately, corporate members dropped out of the coalition; as the grand alliance unravelled, the bill languished in the Senate. After Harry Reid, then in a tight reëlection campaign against a Tea Party candidate, dropped it, Rahm Emanuel, the White House chief of staff, blasted the environmentalists’ political ineptitude at a private meeting. (Bartosiewicz and Miley obtained a tape recording.) The big environmental groups had promised the White House that they could deliver a few key Republican votes in the Senate. Instead, Emanuel said, “They didn’t have shit. And folks, they were dicking around for two years. And I had those meetings in my office so it was not that I wasn’t listening to them. This is a real big game, and you’ve got to wear your big-boy pants.”

As the political process in the United States has become arguably more corporatized, a fact of life that whatever is left of the “environmental movement” has become increasingly inured to, the game has become more clearly understood.

Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger writing in Yale Environment 360, The Flawed Logic of the Cap-and-Trade Debate, adopt an Ecological Modernist perspective, saying “both (James) Hansen and those he criticizes focus on pollution regulation and pricing to make fossil fuels more expensive, rather than on innovation to make clean energy cheap. This approach ignores the history of technological breakthroughs, which has primarily been driven by public investment. And public investment in clean energy is what is needed today, because no effort to achieve deep reductions in carbon emissions, domestic or international, will succeed as long as low-carbon energy technologies cost vastly more than current fossil fuel-based energy.”

Both Ecological Modernists and traditional conservationists agree that ultimately, the environmental movement needs to learn to win with more effective strategies. That means not only what it communicates but how. What had been won and lost in the courts or in the halls of the House and Senate must now again be communicated to people, participating in the free market of capital and ideas. Ironically this harkens back to the age of earlier activists following the first Earth Day.

As Lemann notes in the New Yorker, “Earth Day’s success was partly a matter of timing: it took place at the moment when years of slowly building environmental awareness were coming to a head, and when the energy of the sixties was ready to be directed somewhere besides the Vietnam War and the civil-rights movement… Earth Day had consequences: it led to the Clean Air Act of 1970, the Clean Water Act of 1972, and the Endangered Species Act of 1973, and to the creation, just eight months after the event, of the Environmental Protection Agency.”

The lofty momentum the environmental movement enjoyed for almost 40 years following the first Earth Day crashed and burned in the summer of 2010, when Senate Majority Leader, Harry Reid, announced that he would not bring to a vote a bill meant to address the greatest environmental problem of our time—global warming. The movement had poured years of effort into the bill, which involved a complicated system for limiting carbon emissions. Now it was dead, and there has been no significant environmental legislation since. Today’s environmental movement is vastly bigger, richer, and better connected than it was in 1970. It’s also vastly less successful. What went wrong?”

There was little thinking about what might occur should the technological interventionists get it wrong. And get it wrong they did in the deserts of Southern California. A plethora of large solar technologies, developed at Sandia Labs in the 1980’s were trotted out as “shovel-ready” once ARRA stimulus funds became available. Many of these technologies like Stirling engines https://share.sandia.gov/news/resources/releases/2008/solargrid.html were overly complex and difficult to manage, yet were to be deployed in huge numbers. Despite high conversion of sunlight to power, the Stirling engines leaked hydrogen, sounded like a 1950’s lawnmower, and at a test bed in Phoenix, required one human “minder” for each of the 50 units there. Over 35,000 “Sun Catchers” would be deployed at Imperial 2 Solar (which was to be built on a Native American burial ground) (See my film “Who Are My People?” http://whoaremypeople.com) another 35,000 would be built at the companion “Calico” project. The technologies had never been tested at scale, and hence embodied a level of arrogance and poor engineering that was truly stunning. Fortunately that plan was stopped by a lawsuit, Quechan v. BLM.

In the time since, the agenda, advanced by Ecological Modernists has been refuted http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/14/business/energy-environment/a-big-solar-plant-opens-facing-doubts-about-its-future.html, see New York Times “A Huge Solar Plant Opens, Facing Doubts About Its Future.” http://www.kcet.org/news/rewire/solar/concentrating-solar/palen-solar-project-canceled.html

Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger don’t distinguish between rooftop solar close to load and remotely sited industrial solar. Would public investment in rooftop solar implementation yield better results?

The American Environmental Movement had forgotten, quite simply, how to communicate with people, and particularly how to listen, in the face of abuses by corporations and government. Instead, they partnered with those corporations in the name of combating climate change.

“Isn’t it great that the large environmental groups and the utilities can lock arms on strategy. It just happens to be a very high impact strategy…” Bill Powers, PE, from “Who Are My People?” ©2014 Robert Lundahl.

Perception is Everything

By Robert Lundahl

As Jose Ortega y Gasset – a Spanish existential phenomenologist and one of the great philosophical minds of the twentieth century – puts it, man is “a kind of ontological centaur” because he/she is “half immersed in nature, half transcending it”.

In the name of progress, the ideology of modernization demands and justifies the domination of nature to benefit humankind alone.

Thus Hwa Yol Jung of Moravia College writes in the Trumpeter, Volume 10, No 3 (1993).

Unconquering the Last Frontier, about the “Damming and Undamming of the Elwha River,” speaks about the “Ongoing Salmon Crisis” in the Pacific Northwest. The film details how entrepreneurs in the early 20th century sought to dam a river, one that had produced 100 lb. salmon — among the largest in the Lower 48. The motives were power and profit.

Almost one hundred years later, positioned in the corner of the City Council chambers building I began filming a Citizens Advisory Commission meeting, one that would recommend dam removal, and river restoration, or not. The hope was that the genetics of the fish, preserved in hatcheries managed by the State of Washington and by the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe could be re-introduced, and that these wild-adapted stocks would begin to utilize the spawning habitat above the where the dams once stood.

Phil Johnson, Ph.D. Historian. From Unconquering the Last Frontier, ©2014.

There was a quote by historian Phil Johnson, whom I interviewed in the film, which seemed to resonate with Ortega y Gasset’s. I recall Phil’s words:

“Their conception of progress then was keen, and there was so much around them, so much bounty around them, that it was easy to have that kind of belief, a belief that we could tinker with nature, that we could impound a river that was working just fine for a few thousand years, and then we could artificially spawn the river’s salmon and improve it. And yet 60 – 70 years later there is nothing in that river that would contribute to a subsistence lifestyle, whereas before science, before science improved the river, you had an entire community surviving depressions and recessions, eating foodstuffs from that river for decades, and now we have an entire community that realizes what we have done to the river, we might have to undo.”

The frontier that men and women had subdued in the early 20th century, conquered, in the parlance of the day, would need to be unconquered. Two industrial “high-head” power dams on the Elwha were removed beginning in 2012.

As the last chunks of concrete are hauled out from one of America’s great rivers, I am listening to Naomi Klein’s radio interview about her new book, in Changing Everything: Naomi Klein on Capitalism and Climate Change By the National Radio Project. I was here too reminded what Phil had observed.

Klein’s book postulates that it is the structure of “Capitalism” itself that is endemic to human survival in light of climate change. “When fear like that would creep through my armor of climate change denial I would do my utmost to stuff it away, change the channel, click past it, now I try to feel it. But what should we do with this fear that comes from living on a planet that is dying, made less alive every day? …The real trick, the only hope, really, is to allow the terror of an unlivable future to be balanced and soothed by the prospect of building something much better than many of us had previously dared hope. Because the thing about a crisis this big, this all-encompassing, is that it changes everything.”

Old timers living along the Elwha River would say. The younger generation can’t imagine what the river could be again (once restored) because they have no ability to imagine what it once was. Their “platform” is what they know, what they’ve seen. Klein’s introduction to the radio interview addresses the emotional upheaval many people feel in light of a slow, creeping catastrophe, over which they may feel varying degrees of powerlessness.

But we need not feel powerless. The lessons from the Elwha grow more important with each passing year. Our platform of knowledge based on what we have seen and what we know underestimates the generative potential of the planet.

Rachel Hagaman. From Unconquering the Last Frontier, ©2014.

Rachel L. Hagaman (Kowalski), Economic Development Director, Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe

From Unconquering the Last Frontier. @2014.

Rachel Hagaman (See Video) wrote not long ago sharing a remarkable observation.

Hello Robert…

We are getting ready to go fish for chum salmon. I am sure you have heard by now, the fish are already starting to utilize the habitat up above where the projects used to be located. It is awesome, and it is going to keep getting better. I just want to say that I know in my heart that your film and the work you did had a huge impact on the ways things turned out and I am still very grateful to you for that work you did. Well I should go now, but I am hoping the best for you and yours, and wanted to say hello. thank you again.

Rachel L. Hagaman (Kowalski), Economic Development Director, Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe

Restoring the Elwha River was and is not simply a matter of rebuilding fish stocks, righting a historic wrong, and stimulating the tourist economy. It is about re-building an entire ecosystem, mostly by leaving it alone once the man-made impediments are out of the way. Humanity has often recognized the need to adapt, recognize long term values above short term ones, allow for change, and go forward in new ways. The Lower Elwha people demonstrated remarkable consistency, adaptation, patience, and persistence over 100 years while they fought to survive, and eventually restore the river which had sustained them.

When I first engaged with the Lower Elwha Community, at a “Shake,” an all night spiritual event, Bosco Charles, leader of the Lower Elwha Indian Shaker Church spoke to the crowd. Gesturing toward the hard wooden bench where I was seated, he said, “We have guests here tonight. We’re going to have to open up like we’ve never opened up before.” Here was a guy with a film camera (left in the car) and bushy blond hair, not the usual visitor to the church. Over time, the tribe did open up, tell a myriad of stories which became “Unconquering the Last Frontier.”

Perception is everything.

I learned science does not always provide all the answers. Simpler and slower is often better. What we see from our platform, is not always the whole picture, and almost anything is possible.

Klein speaks of a dichotomy between capitalism and climate. Like most “absolutist” statements, I don’t know if this is true, but I do agree with the later half of the thesis. That we have the possibility to allow the terror of an unlivable future to be balanced and soothed by the prospect of building something much better than many of us had previously dared hope.

That is the lesson of the Elwha River and the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe.

Bosco Charles, Indian Shaker Church. From Unconquering the Last Frontier. @2014.

By Robert Lundahl

“There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns — the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.”

-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, 2002

The matter of the construction of large scale industrial solar and wind renewables has been of concern to me since 2010. At that time I embarked on what would become a filmmaker’s life-journey, documenting a massive scale industrial development agenda, justified by “The War on Climate Change,” that played out across the deserts of Southern California.

The justification for siting over 200 industrial facilities across this remote region, characterized by pristine ecosystems and thousands of years of American Indian culture and antiquities seemed specious, as Germany added 500 MW a month of renewable energy on rooftops and parking lots, close to where it would be used.

Spirit Runners, Mojave National Preserve. Photo: Lundahl, “Who Are My People?” ©2014

Through following a series of proposed industrial solar projects, and documenting opposition to them — I came to learn new lessons in the importance of simple things.

It was humbling to film and describe the federal government’s approach to this mega-scale solar industry land development. Public land was leased at bargain rates to project developers from a variety of countries. Project budgets would run up to 2 billion dollars and developers stood in line to receive 30% “up-front” cash grants. The level of complexity was staggering, as was the potential financial reward for industry. The opportunity to stimulate the economic resources of communities through support of local rooftop solar was avoided, while American Indian antiquities were bulldozed.

The pro-large solar argument had been made by the California Energy Commission, as early as Summer, 2010. The California Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) is one of the most ambitious renewable energy standards in the country. The RPS program requires investor-owned utilities, electric service providers, and community choice aggregators to increase procurement from eligible renewable energy resources to 33% of total procurement by 2020. In response, decisions would be guided by “Overriding Considerations” the perceived necessities involved in meeting the RPS standard. Local economy, conservation and culture would take a back seat.

Crucifixion Thorn, Canotia holacantha.

As individuals we may express a preference that the last stands of rare plants like the Crucifixion Thorn not be removed from the planet, or that large solar “Power Towers” like those at Ivanpah, the first utility scale mega-solar installation not incinerate birds migrating along the Pacific Flyway, or that thousands of protected Desert Tortoise not have their burrows graded, their young (and eggs) obliterated, and adults’ habitat removed forever.

We may prefer, politically, that the American “boom and bust” cycles of Western development, be avoided in favor of the slow and steady persistence of communities, hanging on to life in a parched landscape of mysteries and spiritual connection to the land itself.

But the CEC had their marching orders in light of the RPS. Most Americans, rightly and wrongly, assume that amid calls for sacrifice, whether in actual war, or in the so-called “Great War on Climate Change,” things get a little off-track. But as Rumsfeld states in the famous quotation above, we don’t know what we don’t know.

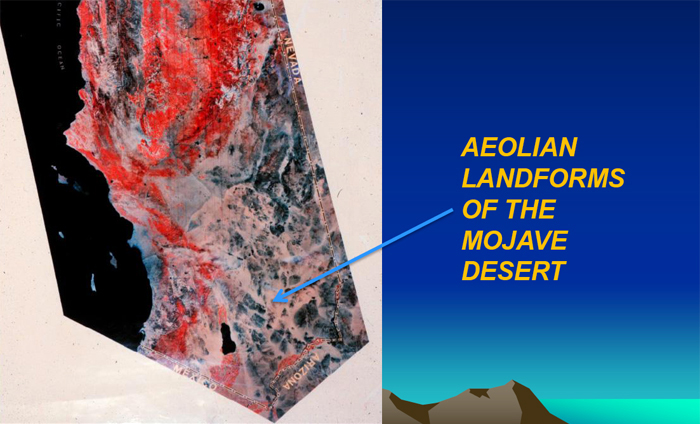

Sand transport paths. “Aeolian Sand Transport Pathways in the Mojave Desert” USGS.

Seen from above, the topography of Southern California is a “Basin and Range” landscape of mostly north-south parallel mountain ranges. Major ranges to the west like the San Gabriel, San Bernardino and San Jacinto Mountains are upthrust from the San Andreas Fault. The Garlock Fault forms the Tehachipis, to the northwest. These mountains are the divide between the semi-arid coastal plain and the Mojave Desert. These ranges block incoming storms from the Pacific, forming “rain shadows,” where descending warm air creates desert conditions.

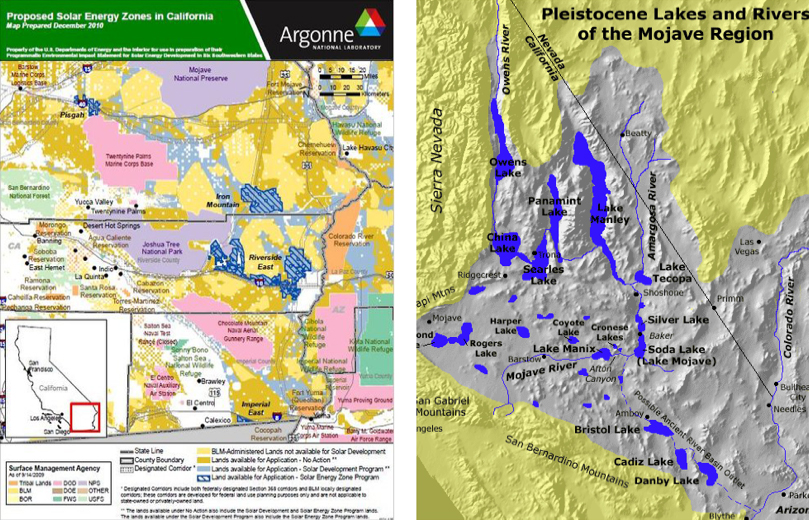

Pat Flanagan, desert conservationist and board member of the local Morongo Basin Conservation Association, was the field biologist monitoring birds at the prototype Solar One facility at Daggett, in 1983. Today, still surveying the ground, she sees sand–wind blown (aeolian) sand, remnant from a vast array of interior lakes, whose drying began in the late Pleistocene Epoch with the end of the last Ice Age.

A side-by-side visual comparison of Southern California solar zones and the location of Pleistocene lakes indicate a similarity in geo-location, which confuses avain species instinctually navigating the Pacific Flyway. This helps account for avain mortality at solar facilities like Ivanpah where birds mistake mirrors for water and attempt to land and rest. Ironically, solar fields built where Pleistocene lakes once filled basins create both a dangerously faux landscape and a new demand for water where none exists today.

In fact, the sand dunes, and sand sheets, unique features in the Mojave Desert ensure the 22 million acres described by the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan for the siting of large solar projects, is on the world’s research map, along with the Sahara, as a world class sand transport laboratory.

Some large scale solar projects are to be put in the Silurian Valley, a magnificently beautiful landscape of purple mountains and unspoiled vistas, and others are to be located in and around Tecopa, a resort and spa area. While this may seem inconsistent from the standpoint of conservation values, it is desirable for companies to locate solar fields on slopes of less than 5%, to have maximum control over the positioning of arrays. This most often means locating them at low or negative altitudes on sand deposits and transport areas. The criteria by which projects are to be sited thus follow construction prerogatives.

The USGS, United States Geological Survey, writes:

About 48% of the entire area is less than 5% slope, and 8.3% is less than 1% slope, the favored slope category, deposits underlying the entire area are either mixed eolian-alluvial

origin, or are fine grained alluvial deposits, and thus are susceptible to eolian dust and sand transport, especially after disturbance. In addition, in this slope category, 89% of the area is susceptible to flooding based on the age and geomorphology of alluvial deposits. These maps are examples of several we present for decision-making with respect to hazards and ecological attributes in the face of climate change.

The Silurian Valley, in particular, demonstrates the myriad problems created from a focus on slope as a single determining factor for project siting. 17,000 acres in the Silurian have been proposed for the eventual development of solar and wind. The Silurian Valley is the end drainage for the Mojave River, which sources in the San Bernardino Mountains, and snakes east and north toward Death Valley. The valley is one of the most dramatic examples of a “sand transport area.” Enormous sand sheets bury mountains to the east, driven by westerly winds. The area is a wildlife corridor between two National Parks, Death Valley and the Mojave National Preserve. It is also an avian migration corridor. And, the area is along the auto route from Palm Springs to Death Valley, one of the top destinations for Canadian, French and German tourists, who come for unspoiled vistas.

A study of 77 soil types in the Mojave River Area, San Bernardino County, by the USDA Soil Conservation Service finds that as the as the river descends into basins, taking into account degree of slope, water erosion, and root depth, 31 have a “high hazard” of soil blowing, and 13 demonstrate a “moderate hazard”. These soil types include Bryman loamy fine sand, Cajon sand, Cajon-Wasco, cool, complex, and Lovelace loamy sand.

Photo Caption: Airborne dust from grading private land outside Blythe, California, rises from the desert floor. On desert pavement, a monolayer of pebbles overlies a stone-poor to stone-free matrix of silt, clay and fine sand, derived principally from wind-blown dust. When grading takes place, the desert pavement is scraped away leaving powdery soils, which become airborne, creating Dust-Bowl like conditions. Photo: Lundahl.

It is sand, that very simple and obvious fact of the desert, that the federal government has seemed to ignore in the DRECP. Although large scale projects have been proposed at sand transport locations such as Ford Dry Lake (Genesis) exposing them to disastrous flooding in 2013, even claiming the lives of two company representatives downed in an observation plane surveying the damage, this kind of impact was perceived as disconnected from the whole.

The realization that there is sand in the desert, continually moving, blowing, flowing, relocating in a vast transport system dating back thousands of years and inhibiting construction activities seems to have escaped policy makers and applicants alike. Plants hold sand in place, along with mycorrhizal fungi associated with those desert plants. When plants are removed, ancient sands begin to travel.

Pat Flanagan points out, it is not only about sand, but water.

California has experienced an epic drought of four years duration. The drought has been caused by a resilient high pressure system pushing Pacific Storms far to the North. While researchers indicate there appears to be no direct link to climate change, Marty Hoerling, co-editor of a climate report published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, and a research meteorologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, noted that high-pressure systems have increased everywhere. While climate change makes extreme weather events like the California drought ten times more likely, natural variability plays a much larger role.

Comparing the periods of 1871-1970 with 1980-2013, the authors wrote that there was “no appreciable long-term change in the risk for dry climate extremes over California since the late 19th century.” California has always been prone to drought, as long term residents like Flanagan appreciate. It is especially a fact of life amid the Mojave’s varied “Basin and Range” topography, a fact of life that state and federal entities overlook.

Large solar projects spread across multiple square miles, whose permitting requires water for construction, mirror washing and other activities, may have significantly underrepresented required water usage. Joshua Tree’s Cascade Solar project, at Coyote Dry Lake, requires ten times the water estimated to tamp down and manage sand and silt at the project, particularly during construction, but also during times when the wind is up. Original estimates of .07 acre/feet usage per acre expanded to actual usages of .7 acre/feet per acre.

Sparrow. Lake effect, Cascade Solar, Coyote Dry Lake. Photo: Deborah Bollinger.

Where will the water come from in an arid region that is potentially growing even more arid?

The larger question looms: In light of required grading and soils disturbance on such a massive scale, blowing silt threatens to turn a land of ancient soils and delicate ecosystems into an unmanageable “dust-bowl,” an unusable and unstable sacrifice zone of previously unseen proportions.

Whereas the dustbowl areas of the Great Depression throughout the Midwest were able to remediate themselves by virtue of access to water from many rivers and streams, the same may not be said for the Mojave Desert.

The importance of simple things, and their ignorance, may unleash unintended and cascading consequences.

Overburdened state and federal agencies, under pressure to lease land and permit hundreds of large solar projects across an area the size of Delaware, have overlooked the obvious “beneath their feet.”

Perhaps that is because their feet are not in the Mojave, nor are they in Southern California, but in Washington DC, and Sacramento, and other densely inhabited cities where the Earth beneath their feet is covered with concrete and asphalt.

As Donald Rumsfeld so stated, the unknown unknowns are the difficult ones.

*Over 200 are proposed and with many approaching 8000 acres, that equals 2500 square miles, a potential land area larger than the state of Delaware.

###

©2014, Robert Lundahl, All rights reserved. Reprint by permission only.

Battling Goliath

Originally Published in The ECOreport. By Robert Lundahl.

As a filmmaker I spent four years, beginning in July, 2010, investigating the impacts of large solar development on the deserts of my home state of California.

Solar development in the deserts of the Southwest was initiated as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which included $6 billion for loan guarantees, an amount that was far exceeded in actuality, over subsequent years.