When I was a boy, growing up in Pasadena, California, we played and rode horses on lands and trails along the Arroyo Seco, translated as “Dry Stream,” roughly the location of the Rose Bowl. The Arroyo Seco was not always dry, floods roared out of the San Gabriel Mountains, down and beyond what is now Devils Gate Dam.

The Xaxaamonga, in their native language, are a band of the Tongva people of California. Their language belongs to the Uto-Aztecan family. Xaxaamonga was the name of the Chief, the tribe and the location, where the Rose Bowl now stands.

According to Wikipedia, “above Devil’s Gate, the rapids of the Arroyo Seco are positioned so that the falls make a beating, laughing sound. In Tongva traditional narratives, this is attributed to a wager made between the river and the coyote spirit.”

As Penn State and USC meet to play in the 2017 Rose Bowl, it is not forgotten by this writer upon what foundation the pageantry rests.

Tongva/Chumash Pictographs, Burro Flats

In 1769 the Sacred Expedition led by Fr. Junipero Serra began the process of establishing the mission system and initiating the Spanish colonization of Alta California. San Gabriel Archangel, the fourth mission of the twenty-one, was established in 1771.

In 1778, the mass conversions of the Indians began. As was to be the case in the rest of California under the mission system, contagious diseases of European origin took an enormous toll on the Tongva. Mission conditions were harsh, tedious, confining, unsanitary, confusing, and culturally alien. Population decline was rapid. Though this period of history is often characterized as romantic, it was an unmitigated disaster for California’s Native People.

When the Spanish era ended in the early 1820s, Mexico secularized the missions. And for the Tongva/Gabrieleño, this resulted in a massacre at Las Flores Canyon near the Rose Bowl itself, just at the top of Lake Street, a posh shopping district.

According to the eyewitness account of a Californian named Philippe Lugo, Mexican forces destroyed “the greater part of them.”

I was born in Pasadena on the 21st of December, a sacred day for the Tongva.

Anthropologist Al Knight has described the importance of the winter solstice to the local Chumash and related tribes as follows: “The entire local Native American Indian religious ritual cycle is centered on the moment of winter solstice. It’s like rolling together our Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s celebration in one event.

Condor Image, Burro Flats Pictograph

Perhaps the most detailed description of condor ceremony in southern California comes from the Panes (or bird) festival of the Luiseño. It was described by Friar Boscana of Mission San Juan Capistrano and by Friar Peyri of Mission San Luis Rey in the early 19th century.

Similar ceremonies were held by the Gabrieliño, Cahuilla, Kumeyaay and Cupeño (Kroeber 1907; 2002).” (http://www.tongvapeople.com/villages.html)

We lived in San Marino in what had been an ex-urban area called Chapman Woods, with a little creek, near the Tongva villages of Akuuranga and Alyeupkigna. For the most part, this is hidden history. California elementary curriculum mandates the teaching of Native history, but that history for me was sanitized, romanticized and for the most part irrelevant and inaccurate, context – free. The history of the Arroyo Seco, but a mile or two from my home was not mentioned.

“Who Are My People?,” (2014) (http://whoaremypeople.com) led me on a journey from my youth. Beginning as a rather innoculous “trip down memory lane” – from the Pasadena of my childhood – the film reaches a pitched catharsis in the desert.

Here, modern day Indigenous elders fight international corporations to preserve and protect a small part of what’s left.

In Southern California, complex, successful, and sustainable ways of life were long existing before the arrival of of the Spanish, Mexican, and American armies.

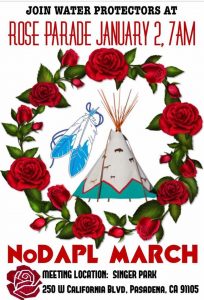

We have been lied to, the actual history covered up for small town boosterism (Rose Parade), and sports events, which had in the recent past, featured Indian mascots. Genocide is a word the 103, 000 fans won’t hear at halftime.

We have been lied to, the actual history covered up for small town boosterism (Rose Parade), and sports events, which had in the recent past, featured Indian mascots. Genocide is a word the 103, 000 fans won’t hear at halftime.

We should be outraged, but in reflection, should take the time now, knowing the event sequence outlined above, to self-educate further on the the life-ways and practices of the people brutally annihilated, and to engage in truth and reconciliation from a contemporary perspective, to honor and respect these native lands, and current–day descendants.